Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH)

What is benign prostatic hyperplasia?

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), or benign prostatic hypertrophy, is an enlargement of the prostate, a walnut-sized gland that forms part of the male reproductive system.

When a man urinates, the bladder squeezes urine out a narrow canal or tube, called the urethra. The prostate surrounds the urethra right at the bladder exit. The prostate plays a role in ejaculation, depositing the ejaculate fluid into the urethra, the channel running through the center of the prostate gland. The prostate gland commonly gets larger as a man ages (this is called BPH or benign prostatic hypertrophy). As it does, it may squeeze or pinch the urethra channel, causing difficulty with urination such as a slow stream, the need to strain, increased frequency, urgency to urinate, and intermittent flow or dribbling.

BPH is the most common disorder of the prostate gland and the most common diagnosis by urologists for males between the ages of 45 and 74. More than half of men in their sixties and as many as 90 percent in their seventies and eighties have some symptoms of BPH.

Although research has yet to pinpoint a specific cause for BPH, theories focus on hormones and related substances like dihydrotestosterone (DHT), a testosterone derivative in the prostate that may encourage the growth of cells.

How is BPH evaluated?

Early diagnosis of BPH is important because left untreated, it can lead to urinary tract infections, bladder or kidney damage, bladder stones and incontinence. Distinguishing BPH from more serious diseases like prostate cancer is important.

Tests vary from patient to patient, but the following are the most common:

- Filling out a questionnaire: Your doctor is most interested in the severity and type of symptoms you have, and how much they bother you or impact your life. A simple questionnaire is a common starting point.

- Urine flow study: During this test, the patient voluntarily voids his bladder and the amount of flow is measured. A special device can help physicians detect reduced urine flow associated with BPH.

- Digital rectal examination (DRE): The physician inserts a gloved finger into the rectum (located next to the prostate) and feels the back of the prostate. Prostate cancers can sometimes be detected as lumps or bumps on the prostate here.

- Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood test: Elevated levels of PSA in the blood may sometimes be an indicator of prostate cancer.

- Cystoscopy: In this examination, the physician inserts a small camera called a cystoscope through the opening of the urethra in the penis. The cytoscope has a camera that allows the physician inspect the inside of the prostate, urethra channel and bladder.

- Transrectal ultrasound (www.radiologyresource.org/en/info.cfm?pg=us-prostate) and Prostate Biopsy: There are two potential reasons for this exam: (1) If there is suspicion for prostate cancer, this test may be recommended. The physician uses an ultrasound probe to acquire images of the prostate and guides a biopsy needle into the prostate to remove small slivers of tissue for examination under a microscope. (2) Your doctor may simply want to know the exact size of your prostate to plan prostate surgery for BPH. In this case, only an ultrasound image will be obtained; no needles will be used.

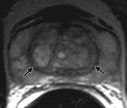

- Prostate magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (www.radiologyresource.org/en/info.cfm?pg=mr_prostate): MRI provides views of the entire prostate with excellent soft tissue contrast.

How is BPH treated?

In some cases, in particular where symptoms are mild, BPH requires no treatment. At the opposite extreme, some men require immediate intervention if they cannot urinate at all or if kidney/bladder damage has occurred. When treatment is necessary, many men will simply require daily medication(s). If this fails to completely treat the symptoms, or if there are signs of damage from BPH, the doctor may recommend minimally invasive endoscopic surgery (no “cuts” into the abdomen) or, in some cases, traditional surgery.

- Drug treatment: The FDA has approved several drugs to relieve common symptoms associated with an enlarged prostate, including drugs that inhibit the production of the hormone DHT and drugs that relax the smooth muscle of the prostate and bladder neck to improve urine flow

For surgery, there are many procedures to choose from, and the choice depends largely on your specific prostate anatomy, and surgeon preference and training. These procedures all have a common goal of widening the urethral channel as it passes through the prostate. Procedures include the following:

- Transurethral microwave thermotherapy (TUMT): In TUMT, a device sends computer-regulated microwaves through a catheter to heat and destroy excess prostate tissue. TUMT does not cure BPH, but it reduces urinary problems.

- Transurethral needle ablation (TUNA): This minimally invasive approach delivers low-level radiofrequency energy through twin needles to destroy prostate tissue and widen the urinary channel, which may improve urine flow.

- Transurethral incision of the prostate (TUIP): In this procedure, the surgeon widens the urethra by making a few small incisions in the prostate gland and the neck of the bladder where it joins the urethra.

- High-intensity focused ultrasound: The use of ultrasound waves to destroy prostate tissue is a promising new area of treatment that is still undergoing clinical trials in the United States.

- Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP): The most common or “gold standard” surgical treatment for BPH, TURP involves the insertion of an instrument called a resectoscope through the urethra to remove the obstructing tissue, almost like removing the core from an apple, thus widening the channel.

- Laser surgery: When a TURP procedure is done with a laser instead of traditional scraping, the procedures are similar although differently named, depending on the type of laser used. They include Holmium Laser Ablation (HoLAP), PVP or Greenlight laser. The physician passes the laser fiber through the urethra into the prostate and then delivers bursts of energy to vaporize obstructing prostate tissue.

- Open surgery: For very large prostates, traditional TURP and laser surgery may be ineffective. In open surgery, the surgeon makes an external incision and removes the enlarged tissue from inside the gland. The entire prostate is not removed, but rather the outer “shell” or capsule of the prostate remains.

- Holimum Laser Enucleation of the Prostate (HoLEP): this is a minimally invasive version of the traditional open surgery, reserved for large prostates. No incision is made. This is a specialized type of procedure currently performed only by select centers in the United States. The procedure duplicates open surgery, with a shorter time requiring a urinary catheter.

Locate an ACR-accredited provider: To locate a medical imaging or radiation oncology provider in your community, you can search the ACR-accredited facilities database.

This website does not provide costs for exams. The costs for specific medical imaging tests and treatments vary widely across geographic regions. Many—but not all—imaging procedures are covered by insurance. Discuss the fees associated with your medical imaging procedure with your doctor and/or the medical facility staff to get a better understanding of the portions covered by insurance and the possible charges that you will incur.

Web page review process: This Web page is reviewed regularly by a physician with expertise in the medical area presented and is further reviewed by committees from the American College of Radiology (ACR) and the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA), comprising physicians with expertise in several radiologic areas.

Outside links: For the convenience of our users, RadiologyInfo.org provides links to relevant websites. RadiologyInfo.org, ACR and RSNA are not responsible for the content contained on the web pages found at these links.

Images: Images are shown for illustrative purposes. Do not attempt to draw conclusions or make diagnoses by comparing these images to other medical images, particularly your own. Only qualified physicians should interpret images; the radiologist is the physician expert trained in medical imaging.

This page was reviewed on January 21, 2014